Not New

One of the longer-term projects I am working on is what I’ve tentatively been calling “Writing Our HSItory,” which Is part of a somewhat-larger concept, our Pioneras/os. As I noted in my introductory article:

Starting more than a half-century ago, Chicana/o students, staff, and faculty at UC Davis began to organize for Chicana/o Studies, into groups for self-help and advocacy work, and to hold the university accountable for improving the educational opportunities available to the state’s marginalized communities. This project begins to tell those stories. From a symposium organized by the United Mexican American Students (UMAS) in 1968, the adoption of the MEChA model–the first in the nation, to helping defeat the anti-farmworker bill, Proposition 22 in 1972, UC Davis has been a leader, a Pionero. It is imperative that we document that story, share it with the campus community, and use it to motivate further change.

And, as has happened throughout my training as a historian, I have uncovered evidence of ideas articulated long ago that are again in the contemporary conversation. Three of the more remarkable examples of this phenomenon can be found in the Chicanx rights movement from the late 1960s.

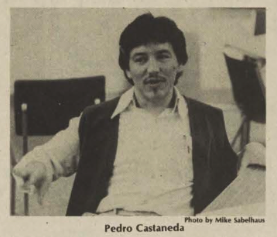

The first is the idea of an asset based view of students, rather than a deficit based view. That is, students who institutions of higher education label as deficient in their preparation or in possessing the skills necessary for acquiring a post-secondary degree are actually neither but rather have talents and potential that society fails–because the failure goes far beyond just universities–to develop. In 1966, the National Education Association of the United States published a report, “The Invisible Minority: Report of the NEA-Tucson Survey on the Teaching of Spanish to the Spanish Speaking.” The report is based on the observation that teachers in Tucson, Arizona “have chosen to recognize the Spanish-speaking ability of Mexican-American students as a distinct asset and to build on it rather than to root it out” (vi). In 1980, Pedro Castaneda, a member of the UC Davis Education department, told a Chicano symposium that “Differences in culture and language must be recognized as resources instead of deficits.”

In the case of UC Davis, we revived this concept starting in 2019 with our report, “Investing in Rising Scholars and Serving the State of California: What it Means for UC Davis to be a Hispanic Serving Institution.” The label of a “Rising Scholar” was adopted from the article “Beyond a Deficit View,” written by Byron P. White for Inside Higher Ed in 2016 and makes the case that “administrators and faculty members desperately need a new language to characterize minority, low-income and first-generation students.”

It’s possible, I suppose, that the reemergence of this concept has been done with the knowledge of its roots stretching back more than a half-century. But I am not so sure. For one, of course, credit should be given to those that first articulated this idea. But, more importantly, I think emphasizing this point hammers the point that not enough progress has been made. The knowledge that students excluded from higher education have talents and potential that we have failed to recognize makes it discouraging and undermines arguments about “progress.”

Two more examples I found in the archives are from the UC Davis newspaper, Third World Forum. In May 1976, they published an opinion piece that asked the question: “Bar, LSAT, SAT Bias?” In the first of a series “concerning minorities and standardized admission tests,” the author observed “Those students who come from middle and upper class families which teach Anglo-American values and skills” do well on standardized tests. The inherent bias of standardized tests such as the SATs has been well known for some time and finally in 2020, the University of California eliminated standardized tests in admissions decisions, the California State University system followed in 2022. The second example, was a two-part series from 1979 (Oct. 9 and Oct. 23) on “How our health system fails minorities.” Long before the Covid pandemic exposed the failings of American healthcare, the journalist made clear the “health care system not only fails these minorities through the omission of essential health services; it also actively discriminates against them in manifold ways that place them at continuing disadvantage.”

In other words, these are not novel considerations only recently discovered following much hard work which we (society, policymakers) were innocently working in ignorance. The criticisms are identical. Of course, the failures to make corrections to these inequities are not the fault of those who have long objected to or have worked to undo the harmful effects of racism. At best it’s apathy, at worst it’s a deliberate commitment to white supremacy.

It occurred to me that this phenomenon is probably due to the fact that because much of what I study are historically marginalized groups and the ideas that support their liberation or advancement have not been enough to achieve their desired results, even after decades, so that they come in and out of relevancy. Nevertheless, it’s easy to imagine the frustration and anger many would feel knowing they are screaming into a void.

Views my own.